By Anelise Leishman

So, who’s older?

People love to ask this question. The script is one we’ve memorized well: My sister was born first, but there’s just one minute between us, so it doesn’t count. It was a C-section, my mother explains, and they were side by side. Really, it just came down to whose foot the doctor grabbed first.

Our mother tells this story to create the illusion that neither one of us had a head start, an advantage. “It doesn’t count” is an incantation we know by heart, a mantra that tiptoes around the compulsion to compete with one another. With curious new acquaintances, we find ourselves repeating our mother’s words: It doesn’t count. As far as we’re concerned, we came into this world at exactly the same time.

What’s it like?

This is the part where I tell them everything they ever wanted to know. I love being a twin, I say. When I’m at a party, there’s always someone I know. We borrow each other’s clothes, so we have double the outfits to choose from. It’s like having a built-in best friend.

Except that living with her is almost like living alone. Whenever we occupy an empty space together, I’m reminded that for a long time, being together was the only “alone” we knew. We can share a room as comfortably as we shared our mother’s womb.

One time, we walked into a public restroom together and chatted to each other from our separate stalls. When we stepped out to wash our hands, a woman was standing by the sinks with a perplexed expression on her face. Then she laughed—and told us she thought that we were one person, talking to herself. This has happened more than once.

Do you have a secret language?

There was never a time when we couldn’t understand each other. We’ve always had inside jokes—even as infants, all we had to do was exchange a look, a sound, a word of nonsense, and we would break out into wet baby giggles. We took part in a twin study that set out to determine whether the secret language phenomenon was real. The researchers decided it wasn’t, but they rewarded us for our gibberish all the same. We saved the money and used it to buy laptops for college.

Can you read each other’s minds? Like twin telepathy?

I’ve heard roommates, soul sisters, and besties say that they’re totally on the same wavelength, so in sync it’s ridiculous. I’ve always had a hard time forming these kinds of female friendships because nothing has ever come close to the one I’ve had from birth.

Sisters grow up together like two of the same kind of plant in the same pot. But twins are two stems from one stalk. The tiny little pathways in our brains mirror each other, drinking up the same water, drawing from the same context. It’s not that we read each other’s minds—they just tend to arrive at the same place at the same time. Even in our sleep we share a consciousness. More than once, we’ve woken up only to discover that we’ve had the same dream. We don’t finish each other’s sentences only because they don’t need finishing—we already know what comes next.

Did you ever switch places?

I wonder if the obstetrician paused before he yanked that little foot. Probably not—I’m sure that for him, it was just another Saturday night. But if he had picked one of my feet instead, I would be Alexandra, and she would be Anelise. Would it matter?

Those curious new acquaintances like to speculate: surely some hapless nurse must have mixed up our hospital bracelets or bassinets, so there’s no possible way to know who started out as who. And then I ruin their fun by telling them how our parents did their due diligence, keeping track of us by freckles and birthmarks, and how they painted Sasha’s toenail bright red before we even left the hospital.

Not long after we were born, a family friend gave us matching rag dolls. They were friendly and round and made of the softest cloth, with eyelet lace bibs and old-fashioned nightcaps. These dolls were alike in every way except one was dressed in blue and the other in pink. We shared a room, our twin beds head-to-head along one wall, and we held the dolls tight while we slept. Once we were old enough to know that such things deserve names, we cleverly christened them “Blue Baby” and “Pink Baby.” Then, when we were about three, Sasha decided she liked pink better, and I declared that I liked blue more anyway. So we reached across our twin beds and swapped. Just like that.

I have a picture my mom took before we left for our first day of preschool. We are wearing the same dress, but in different colors—full-on matching was out of the question. My hair is long and hers is short, an executive decision made by our mother when even we couldn’t tell ourselves apart in photographs (Mommy, which one am I?). But best of all is the chunky jewelry around our necks: leather cords with handmade, kiln-fired beads that spell out our names in capital letters. These were mostly for our teacher’s benefit, because even with the different haircuts and outfits, it was hard to keep it all straight: Which one’s the purple one? Who has the short hair again? The necklaces were the most straightforward solution. But I can’t be sure whether we swapped them from time to time when the teacher wasn’t looking. No one would have been the wiser.

By middle school, our teachers had learned to put us in different classes, and after countless viewings of The Parent Trap, we decided to switch places for April Fools’ Day. We wore each other’s clothes and carried each other’s books. Our favorite teachers could tell us apart and played along; the others didn’t know until we told them at the end of the day. But we never got in trouble for it—we were good girls. This became a tradition that lasted until high school graduation.

Blue Baby still lives in my nightstand, sitting upright in a darkened drawer. Her cloth face began fraying years ago, but her painted features have been preserved thanks to my mother’s careful fingers and a bottle of clear nail polish. I can’t help but wonder where Pink Baby is now. I haven’t asked.

Do people mix you up a lot? Can your husbands tell you apart?

It’s not an issue for the people closest to us. Once when we were in line at an ice cream shop, my husband unwittingly touched Sasha’s waist from behind, thinking she was me. That’s the only instance I can recall. And I can’t blame him—we look awfully alike from the back. I once made the same mistake with my husband’s brother, and they aren’t twins.

Every now and then—sometimes several times in one day—I will walk by, run into, or stand in the elevator next to a perfect stranger who thinks I am Sasha. If I’m passing them in the hallway, a simple smile and nod will do the trick; no need to embarrass them. But if they call me by her name or try to strike up a conversation, I have to break the news to them: Sorry, I’m actually her twin sister. They’re always so apologetic, but I reassure them that it’s fine. How were they supposed to know? I tell Sasha every time I have one of these interactions. That’s never happened to me, she says.

The lines blur; we respond to each other’s names, whip our heads around whether or not it’s the right one. A friend walked up to me after class one day, looking ashamed. “I’m so sorry I called you Sasha,” she said. I told her not to worry about it because truthfully, I hadn’t even noticed.

Sasha texted me the other day: It finally happened. She didn’t need to tell me—I knew immediately what she was talking about. Someone had finally mistaken her for me.

Are you ever competitive with each other?

Maybe you’ve heard about the multiverse theory. Maybe you’ve thought about it a lot. You can think about it in terms of an infinite number of yous in an infinite number of universes. The other you could be a quarter inch taller, or a little more decisive. Maybe she’d be prettier than you. Get better grades.

Now imagine this other you drops into your universe—or maybe you’ve dropped into hers?—and every day you see the same circumstances, the same potential playing out right beside you in mirror image. Everything she does well that you don’t is a failure to live up to your biology, and the proof is right there in front of your eyes. How could you not be competitive?

As kids, we fought about petty things: I ate cereal from her favorite purple bowl, she wore my best sweater without asking. Someone got the bigger half. Sometimes we’d yell: I hate you! You’re ugly! And Mom would laugh and shake her head, because how can you say that when you’re practically looking in a mirror?

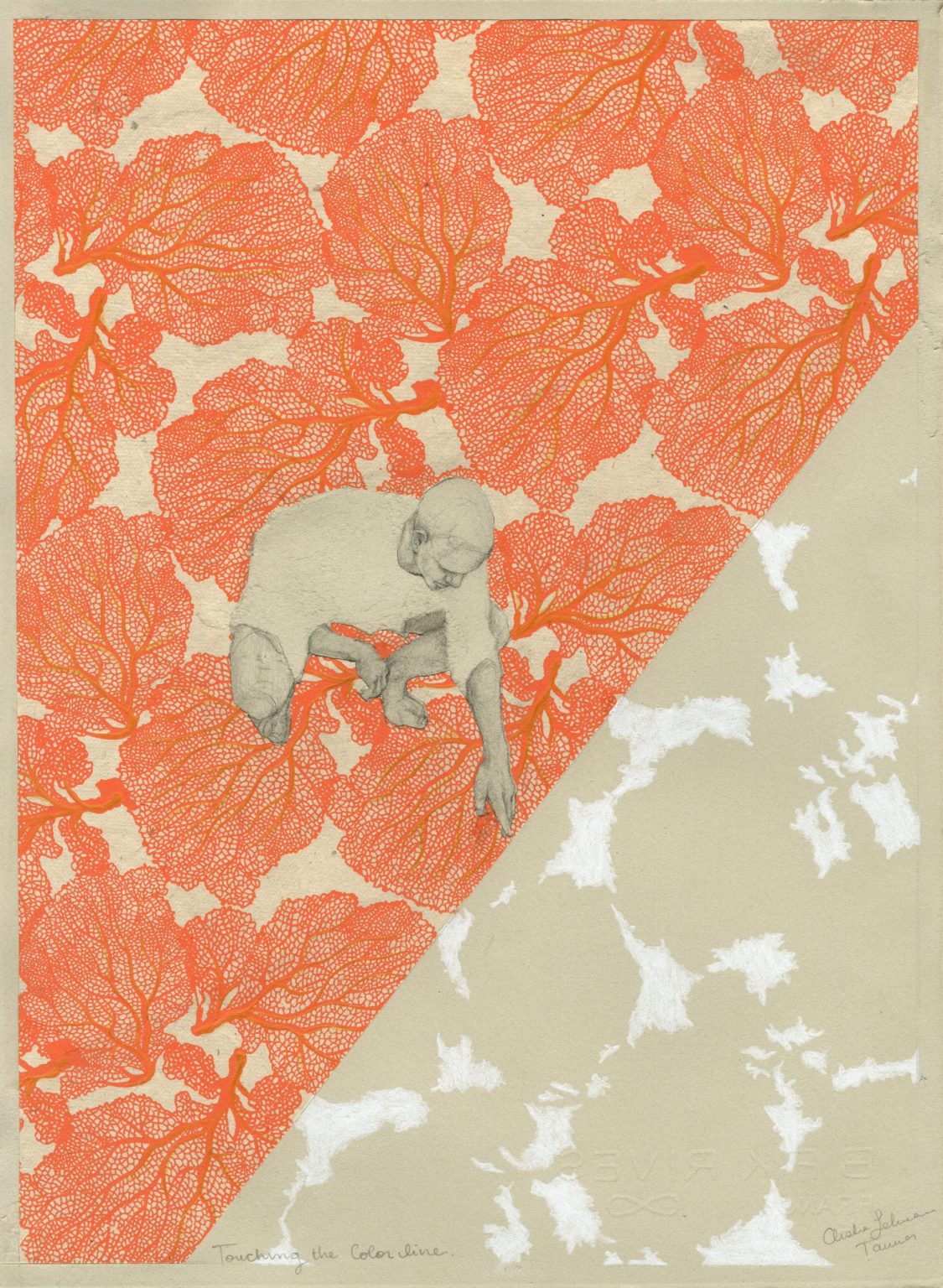

What our mother couldn’t understand is the phantom pain that comes with looking too closely at the reflection. Each success and failure sends echoes that reverberate and multiply—echoes of relief, superiority, jealousy, shame. We see our imperfections in each other, and those perceptions tangle like vines until it’s impossible to tell which root they came from. Twin life is endlessly complicated.

It’s never a big deal, though. Each fight ends with a truce in the form of an inside joke, a word of nonsense, a finished sentence that brings us back on the same page.

*****

Our mother had a womb all to herself. She was born in 1956, along with all the eggs she’d ever have. One of them was us.

The egg split sometime in ’94, when our parents were right on the cusp of their forties. This means that for almost four decades, Sasha and I were waiting, dreaming together as one egg, one body.

Parts of us have existed longer as one than we ever have as two. We’ve spent more years together than we have spent apart. When I realized this on my way home one day, I burst into tears on the bus. I started thinking about which one of us will die first, and which one of us will have to live through it.

We formed together, arms and legs and hair and fingernails, tiny pathways in our brains and hearts and lungs that mirror each other. With one minute between us, we are two people that life can only push further apart. But we speak with the same voice, dream the same dreams. We are two twin stems reaching for the same sun.