By Cristie Charles

I grew up as a daughter of the BYU College of Humanities. I attended its events; I was trained in its language; I even knew its geography.

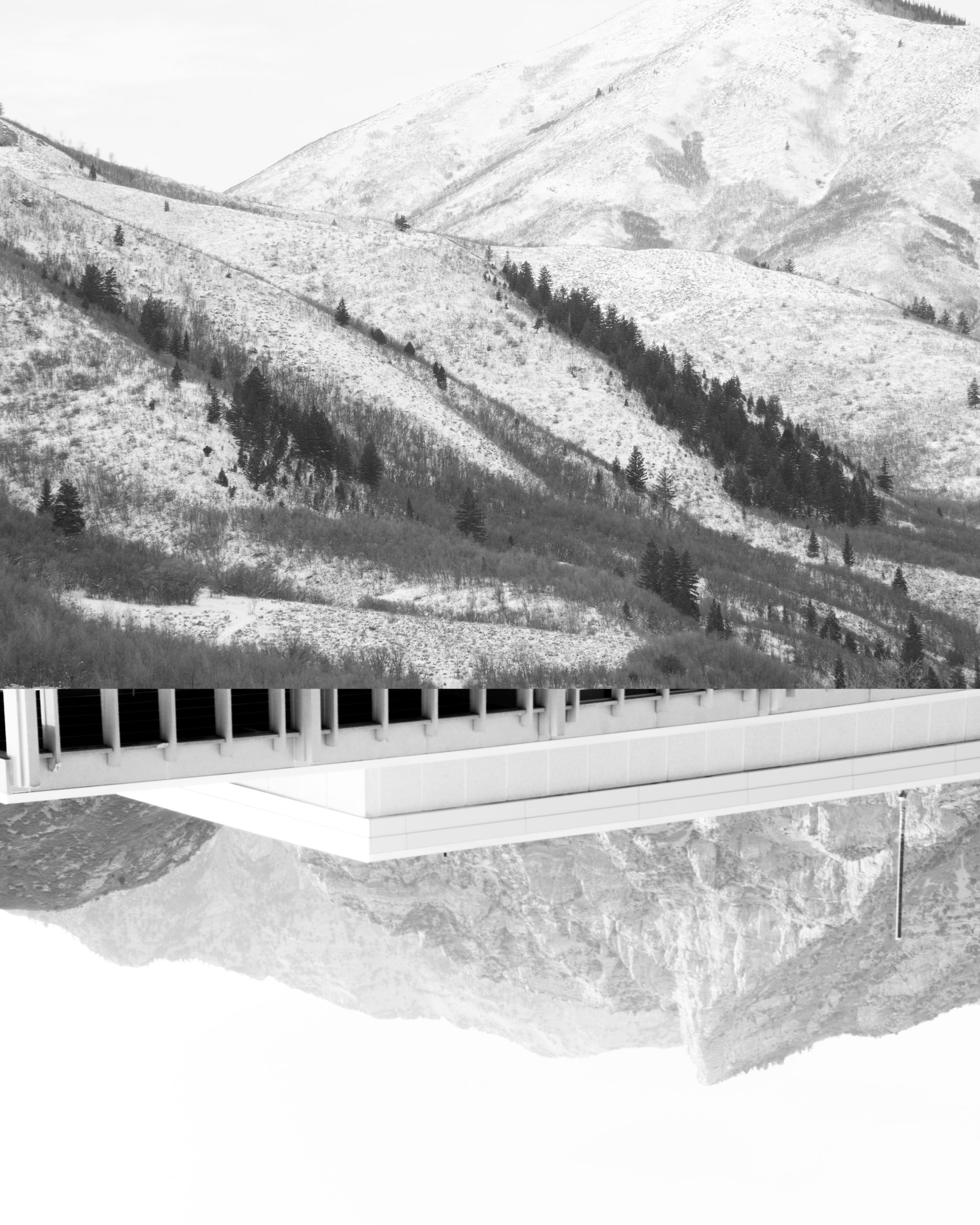

ENTER TO LEARN

Before I was eight I knew how to enter the west side glass doors of the JKHB, walk up the white-with-gray-flecks pilgrimage stairs, and knock on the thick wooden door of my dad’s office. Although back then it was less Enter to Learn and more Enter to Dig Through My Dad’s Pen-and-Pencil Drawer for a Quarter to Put in the Miraculous Ice Cream Sandwich Machine. I’ve still never seen anything like that whirring contraption that culled from its icy depths a paper-wrapped treat and pullied it up in a little metal assembly-line elevator. The best part was yanking the square door upward—upward! (the door had hinges on the top)—and reaching in to claim my cool reward. Clearly, I thought as I licked my fingers post-ice cream and eyed my dad’s book-laden office, he had the best job in the world.

Plus the name on the office across the hall read “Jay Fox” who inevitably, I determined, must be related to Michael J. Fox.

I cut my teeth on English department Faculty Follies nights and English Society performances. I watched in fascination and a little horror as my parents regularly performed “The Transformational Grammar Blues,” and Tom and Louise Plummer always sang a song that ended in them basically just making out on a piano bench. It was the stuff of legend. In familiar 2084, the JKHB auditorium, I watched performances of A Winter’s Tale and The Scarlet Letter (a musical! English-department style, of course, with interrupting literary theorists and five different Hesters). Peter Sorenson’s spot-on imitations of general authorities at first took me by surprise, but I learned to get used to the intermingling of churchness and schoolness at BYU events, even the funny ones.

As I moved into high school, my humanities horizons expanded, and I became obsessed with all things French: I bought a beret, attended the French International Cinema films, went to the BYU French Fair, memorized the map to Paris, started reading Le Livre de Mormon, and carried in my backpack a quote from The Little Prince: “On ne voit bien qu’avec le coeur. L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux.” Translation: “One sees clearly only with the heart. What is essential is invisible to the eyes.” I might not have had the faintest idea of what those essential, invisible parts of life were, but I knew the quote meant something deep, so I fancied myself quite erudite.

Each semester through my high school years, my English professor parents invited their students to our hastily spic-and-spanned yet still book-littered home to watch movies like The Pirates of Penzance or the linguistics bestseller Muvver Tongue. I’ve seen that one about 52 times. The students would frequently ask me questions that had clearly come up in class like, “Are you the daughter with the boyfriend or the one with the plaid Doc Martens?” As the oldest child, I was usually both. It was then that I discovered that there were entire classes of 20 or 30 people at a time who, while discussing obscure Victorian poetry or examining the History of the English Language, also acquired brief snippets of my teenage history. And I caught a few snippets about them, too. I remember looking around the room once during a Nicholas Nickleby marathon trying

to figure out which student had just had their appendix removed. Or which one had cried in my mom’s office. There was nothing as cool as people slightly older than me, so I paid close attention. For example, Farrell Lines, if you’re out there, I’ll always remember you as the cutest guy my parents ever showed linguistics videos to.

As I grew, the language of the humanities mingled with my vocabulary, my thoughts, my core. I found myself (yes, sometimes pretentiously) throwing out words like post-colonialism, ideological state apparatus, and Derrida (pronounced in the correct French way, of course). Meanwhile, as my testimony grew, the languages of both the spirit and my education intermingled so much that I had to pry them back apart in order to comment in my high school classes.

In fact, my first memory of feeling the spirit was also sponsored by the College of Humanities. On an Honors English class trip to Arches National Park and Moab, my parents thought it would be enriching for me—an eight-year-old—to tag along and camp along and pontificate along with their students. I sat among them with my clipboard, admiring a red rock formation and writing my feelings as per the class assignment, frequently observing the other students to make sure I looked appropriately studious. On Sunday morning, we gathered to sit on a ruddy cliff overlooking Dead Horse Point for a testimony meeting, and I listened to a curly-haired freshman in a blue plaid shirt and jeans admit that she’d made a lot of bad choices in the past and had only just heard of the Gospel and joined the church right before she applied to BYU.

It had never occurred to me to imagine a life without the gospel, and at that thought, inexplicable tears streamed hotly down my sunburned cheeks, dropping into the red dust. I buried my embarrassed head in my hands, sobbing. Not understanding exactly what was happening, I looked to my dad who whispered that this was probably my first time feeling the Spirit. But more than that, this was my first empathy moment, when the Holy Ghost helped me understand what someone else was feeling, when I could imagine myself in someone else’s situation and connect that to my own experience—when I simultaneously saw my own blessings and mourned another’s lack.

Whether this was triggered by my participant observation of a humanities class in action that weekend, I don’t know, but I suspect it was. That type of empathy moment I had in red rock country resides at the core of studies in the humanities. Theorist Judith Butler describes it this way:

“The humanities give us a chance to read across languages and cultural differences in order to understand the vast range of perspectives in and on this world. How else can we imagine living together without this ability to see beyond where we are, to find ourselves linked with others we have never directly known, and to understand that, in some abiding and urgent sense, we share a world?”

Note that Butler says read across languages and differences. For it is through words that we connect, and through the vocabulary of narrative that we first learn another person’s perspective and then recognize the fundamental humanity in it. This effort differentiates the humanities from simply the study of humans; we not only choose to describe the people around us, we seek to understand them, to connect, and in church terms, to learn charity.

When I finally (legitimately) entered to learn as a BYU freshman English major, I was eager to read as many perspectives as I could. After years of attending the College of Humanities events, I felt like I’d finally arrived home. I spoke the language (the Muvver Tongue) and even had a few French poems memorized. I knew the geography; stepping around the studied-out, seemingly dead bodies in the basement of the JKHB came naturally to me. And I was on friendly terms with many professors, even referring to one as “my brother” because he’d lived in my family’s basement when he was first hired at BYU. Choosing between classes in the Humanities section of the BYU Catalog made me salivate; I felt I’d approached the proverbial Ice Cream Machine, ready to retrieve my cool reward.

And rewarded I was. In almost every class, I found delectable delicacies. I listened, rapt, as my Introduction to English Studies professor Catherine Corman Parry taught about the depths of love as we read John Donne’s “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning.” The leaning compass, the airy, stretching gold—nothing could be more romantic. I explored stereotypes and prejudice in a class on Primitivism in modern African American literature. I discovered seeds of Jane Austen’s genius that were planted as a teenager in her volumes of Juvenilia. In French and Italian Cinema, I learned how to read cinematic themes of empathy in the turtle soup in Babette’s Feast. I regarded utter loneliness in remote Saskatchewan in Gabrielle Roy’s Un Jardin au Bout du Monde (translation: A Garden at the End of the World). Even comparing the felicity of the King James versus William Tyndale translations of the Bible taught me to see detail and subtlety when confronting differing interpretations.

Not to brag (okay, to brag), but on London Study Abroad, after watching Kenneth Brannagh’s four-and-a-half-hour uncut turn-of-the-century Hamlet, I joined my fellow students and lay in front of the coach in protest, refusing to leave Stratford-upon-Avon and end a perfect evening. Then back in Provo, I moved into the French House where I lived among “houses” and peers from all over the world and finally gained the language fluency I sought.

It was a feast. Like dozens and dozens of ice cream sandwiches. I even stayed for a master’s degree because I hadn’t quite finished dessert.

GO FORTH TO SERVE

And then I had to leave.

Like our First Parents, my husband, infant son, and I left the BYU Garden and drove into the wilderness across the America I only knew from books. We made just the most essential stops: getting gas, nursing the baby, visiting church history sites, and touring prominent authors’ homes. My husband began an intense PhD program and we moved into a tiny apartment on the 26th floor of an ancient cement high-rise just across the river from downtown Boston. This is it, I thought. My chance to put my education to the test.

Our church ward met in the cafeteria of a high school designed by the architect of the prison, and it showed. Then we upgraded to a renovated boiler building, complete with flywheels and

machinery in the rafters overhead. I felt blessed to connect with the many other BYU-educated church members there for graduate school at Harvard and MIT. My female friends and I attended lectures; took our children to art museums, cultural events, more authors’ homes, and met to discuss literature in depth—a life, I thought, that fulfilled most of my humanities dreams (minus the grad school poverty that we counted out in quarters at the laundromat).

And this sufficed until one day in Relief Society. Donna Marie, a hippie-esque Aikido master with unconventional teaching methods (she often brought a sword to church), unhappy with our responses at the beginning of class, decided to force (at sword-point) every woman in the room of about sixty to answer her leading question. She went down each row one by one, singling us out. When she reached Madeleine, an extremely shy 80-year-old Haitian immigrant sitting behind me, things got tense. Madeleine stayed silent, eyes averted. Donna Marie asked her question a little louder, like an American tourist. Even without turning to see Madeleine in her long printed dress and dyed-black bun, I knew she was in distress. Maybe her breathing picked up, maybe her silence loomed, but my humanities-developed instincts told me she needed backup.

I realized that as a native French speaker Madeleine clearly didn’t understand the language of the question. And there I was sitting right in front of her, with only slightly rusty French skills, perfectly poised to turn around and explain it to her. But then I hesitated. I started imagining the reactions from the academic women around me if I made an obvious French mistake. I worried about disrupting the flow, seeming rude, and drawing the wrong kind of attention to myself. What if I couldn’t explain things well enough in French and I just made everything worse? My sudden self-consciousness stiffened my neck and held me silent to my chair. Eventually, Donna Marie gave up and moved on, but I remember at the end of the meeting, finally turning to see Madeleine’s defeated posture and her quick retreat. I knew I had failed my first real-life exam.

Soon after, my husband, two sons, and I drove through autumnal New England bliss to visit a cosmopolitan aunt living in Montreal. Still feeling rusty, I decided that since it was a bilingual city, I would not attempt to speak French for fear of, to put it frankly, biffing it. English would do. I planned to simply declare “I don’t speak French” wherever we went, and people would magically accommodate us with no unnecessary awkwardness. This worked perfectly until we entered a French bookstore. We wanted to stock up on hard-to-get titles (okay, on French comic books), and while I was staring at a shelf of Asterix and Obelix, a man in a green apron approached and asked, “Puis-je vous aider?”

I answered happily, “Oh, I don’t speak French.” And as I turned back to face a row of French book titles in a French bookstore with French music playing in my ear, I knew I was caught. His lilting English “Okay, may-I-’elp-you?” resounded like the cock’s crow. For the second time in mere weeks outside the Garden, I had denied the very education I was attempting to test. Not only had I opted out of Kenneth Burke’s proverbial conversation, I had refused to even enter the parlor at all. Despite all my academic pontificating, I had clearly developed a blind spot. A beam in my eye. My erudite French quote from high school hit me in the face: What is essential is invisible to the eyes.

The Little Prince’s fox was right after all. I had thought that all I had to do was reach into the Ice Cream Machine of academia and simply claim my education, that lessons in vocabulary and theory were enough. But I had missed the most important step, the meat and vegetables of the humanities: action. And, therefore, I had remained only a tourist within the human conversation, not actually fluent in it.

On the dark, wet drive home to Boston my betrayals haunted me; I had effectively denied my intellectual and spiritual birthright. But the beauty of a cock’s crow is that it often precedes an awakening. And so, like prophets I’d read about, somewhere between Saint-Armand, Quebec

and Brookfield, Vermont, I experienced a mighty change of heart. I decided it was time to drop my fear-filled facade, pick up all the humanities skills I had, and enter the conversation, mistakes or no. The next Sunday I spotted Madeleine and asked to sit next to her. I showed her the French-language Relief Society manual I had just purchased, and asked “Puis-je vous aider?” She looked surprised and relieved and simply nodded her head. I began translating the lesson in halting, uncertain French. Sometimes she laughed at my circumlocutions, but now I felt I could laugh along with her.

Thus began a deep friendship and many years of French translation in Relief Society. But more than that, I learned to seek out other people’s stories as eagerly as I had approached my classes. By the time we left Boston, I could look around the boiler building church and tell you that before meeting the missionaries, Beverly had joined the peace corps and converted to Buddhism; that Jodi, who knew mafia members and dropped all her r’s, had a strong testimony of the Restoration yet still watched Catholic mass everyday on TV; that Monique finished nurse’s assistant school because her taxi-driver husband had left her to care for her son alone; that Bev loved to act in movies as an extra whenever Hollywood came to Boston; that Roberta, who often put my name on the temple prayer roll, had had an infant son who died of SIDS while she was taking a shower; and that, to Madeleine, living in a tiny apartment in a poor corner of Boston was better than the prospects she had in Haiti. And that she sent money home to family every week. I learned that even Donna Marie herself had studied Aikido to deal with the stress of becoming a widow twice-over. It was learning these women’s stories and sharing their lives that had finally allowed me to live my education: to be human, to empathize, to have charity.

Today I sit on our couch—the same furniture leftover from grad school—my arm around my curly-haired, red-headed three-year-old daughter, starting a reading lesson. I teach her sounds like sh and v, and we read stories about cats and mats. She’s just learning the fundamentals of language.

Like my parents before me, I teach in the BYU English Department. And although the Magic Ice Cream Machine has disappeared along with the powdered soap in the bathrooms and the H in JKHB, I’m tickled when I think that I now have an office on the top floor like my dad. And I anticipate that someday soon my daughter will run up the remaining pilgrimage stairs to my office to embark on her journey towards fluency in the human conversation.

Works Cited

Butler, Judith. Commencement Address, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, 30 May 2013.

Cristie Cowles Charles currently teaches classes in literature, writing, and global women’s studies at Brigham Young University. She’s lived in Chicago, Boston, London, Zurich, and now resides in the shadows of the Rocky Mountains. She received a BA in Honors English with a French minor ’99 and an MA in English ’02. She’s married to a BYU Professor in Mechanical Engineering and Neuroscience, and they have five magnificent children: four sons and one daughter. Her two oldest children are now undergrads at BYU, one majoring in English and the other in Mechanical Engineering with a minor in Global Women’s Studies. Life feels like one eternal round.