By Megan McOmber

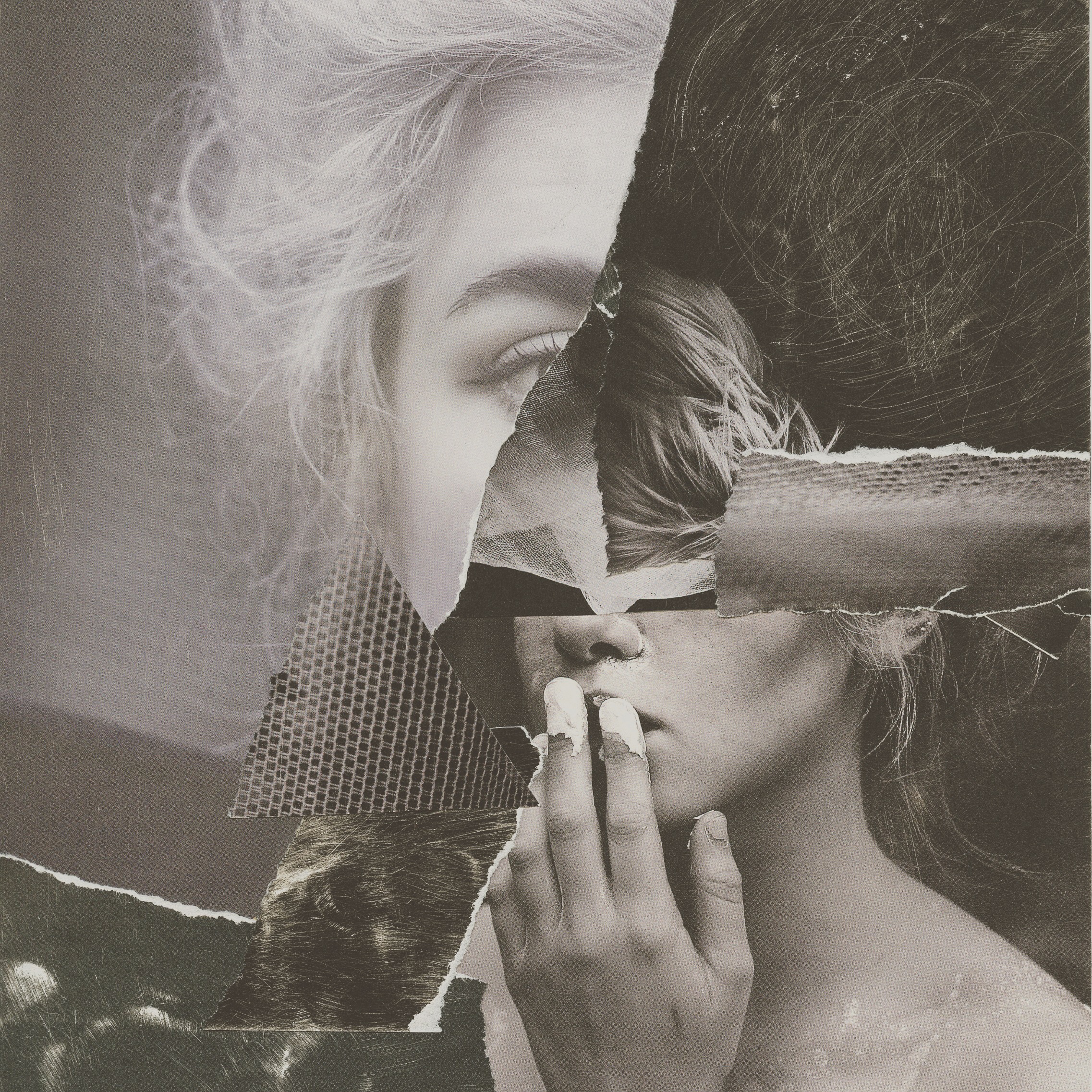

The outer layer of the skin is replaced thousands of times over the course of a human life. We shed ourselves once every 28–42 days. Which is about the same amount of time between my uterus lining shedding itself in a bloody mess. But I lose skin in secret ways. It flakes, speckling the inside of my black leggings, scrubs off in the shower, floats around me in the streaming afternoon sun, glittering, drifting, sparkling like magic.

In medieval times, books were made of parchment or vellum. They were made out of sheep skin. Holes were poked around the edges, then tied with strings to a frame, and pulled tight tight tight. An entire flock of sheep would produce a single book. A whole flock. And when you read these medieval texts, it is pretty surprising that those are the words they thought were the most important to kill an entire flock of sheep for. To spend months stretching and tanning skin. If that is what it took to write down my words, I don’t think I would write anything.

The skin of a stillborn goat was considered the best because it was the smoothest.

My skin has never been soft. Too course. The backs of my arms are filled with bumps. My thighs like chicken skin. No amount of exfoliating, shaving, lotion, or sun has been able to change that. Scars trace up and down my shins from clumsy shaving, bike crashes, scratching. My stomach and hips and breasts are etched with bright white stretch marks that extend in ripples. I graze my fingertips over them, feeling my topography, proof of my daughter’s life once rooted in me.

As a kid I would trace my mom’s arms back and forth. I would sweep my fingertips up and down her forearms, reveling in her softness. As a teenager, I interrogated her on hair removal, she had no hair of her arms and hardly any on her legs. She promised me she didn’t, just genetics. And I wondered how those genetics missed me.

The genetic propagation of dahlias happens in two ways. First, you can dig into the soil and break off a small tuber from the main root bulb. This ensures an identical genetics. That tuber will grow into the exact same type of flower: color, shape, style of plant will be an almost perfect match. Not many people know this, but the second way to grow dahlias are from seeds. Taken from the flower itself this allows for an entirely new variation. The DNA contained in a seed is uniquely its own. Dahlias can be developed from seed to seed, cultivating new plants that have never existed before.

My paternal grandmother, Grandy, loved dahlias. She had dahlias growing throughout her garden. She and I planted dinnerplate dahlias in my childhood backyard, and she taught me about cutting the tubers to grow new plants. I can’t remember if they ever bloomed.

Grandy was a fearsome lady, rough and tumble. Once, as an adult, she punched her sister in the face for sassing her. The sister she punched, later took a rifle, and shot the piano my Grandy was practicing on because the tune was just so damn annoying. Grandy killed mice, ripped things open with her teeth, and cooked blackberry crumble over an open flame in a punch bowl, slowly turning the bowl for hours. In preparation for a family camping trip, she bought a rubber mask of a very realistic looking dinosaur from a thrift store. The next day, she snuck down to the water before any of us kids could jump into the Puget Sound. When we weren’t looking, she slipped under the water, pulled the mask over her head, and then emerged from the waves. We shrieked, clawing over one another, scrambling up the banks, scraping knees and bellies on the rocky beach. When Grandy revealed herself, she was belly laughing—loud, sharp, booming laughter—punctuated by heaving inhales. My cousins and I cried on the beach chairs and in the sand. When we gained enough courage to return to the water, our scrapes stung with salt.

Grandy’s skin was soft. Velvety soft. She had lost hundreds of pounds later in life and her skin hung in ripples, dripping from her back, underarms, and legs. The jowls of her face would rub against mine when she smattered me in kisses. Soft skin flapping, skimming, grazing against my face. Peach skin soft. Like lamb’s ears. Like flower petals.

Her skin is buried deep in the earth now. No longer regenerating, only shedding off. She died in the fall, the petals of her dahlias slowly drying to whispers, slipping to the earth. Her skin and her flowers soft and gone. Every bit of my skin that had touched hers has long shed into the air around me. I grow and my daughter grow cut as tubers, or perhaps plucked as seeds, planted deep in the warm earth. Stretching tight, growing soft, slipping towards the earth.