By Neah DePoe

I’ve touched more teeth than you. Way more. I’ve wrestled and wrenched them down with wires and bands and springs. Cleaned them with chemical-flavored paste. Studied their X-rays and fastened on retainers. Watched their teenaged owners wriggle and writhe in protest in my chair. That orthodontist assistant job was my first introduction to teenagers. They flowed in and out of the office like liquid mercury. Slower than you’d expect, but still they warped through, bumping along and begging for the metal in their mouth to be gone.

I dreaded the 13- and 14-year-olds the most. I really think that they’re another breed. Like we’re all golden retrievers and they’re borzois. Have you ever seen a borzoi? They look like someone tried to piece together a dog from memory after not seeing one for ten years. No ears. This long snout like they tried to swallow a banana whole, and it got stuck right there. Lanky and skinny with prepubescent mustache whips of fur.

Awkward. Gangly. Warped in the wrong spots. Not the shape it was meant to fill.

After a few years, I left the world of teeth and set off to be a youth camp counselor for my church. I had an itinerary that spanned from Utah to Vermont to New York to Missouri and back. I knew there was a chance I’d end up with those borzoi 13- and 14-year-olds, but out of the six weeks in the summer, I also had six chances to be with the older kids. The 16- to 18-year-olds who had managed to morph out of that borzoi shape into something a little more like a retriever. Imagine my surprise when I was assigned 13- and 14-year-olds for the whole summer.

Terror gripped me. I sweated over how I could handle these kids for six weeks.

By the end, I wondered how I could handle being without them.

I met the sun in early June. She wore wire-rimmed glasses and white sneakers. The world spun around her, and maybe she was the one who gave it the original flick that set it in motion. She had it together. A boyfriend. A job as a professional violaist. A published book. Straight teeth. Fourteen years of experience on this earth.

One day, during lunch, I sat under a tree to escape the blistering heat. The sun sat across the grass and nibbled on her salad. Then she saw me, crawled over on hands and knees, leaned back against the tree, laid her head on my shoulder, and cried.

I awkwardly hugged her. “What’s wrong?” I asked, concerned. If she was struggling today, my other kids didn’t stand a chance.

“I miss my little brother,” she whispered.

Part of me—the part wearing latex gloves and holding sharp orthodontist tools—thought, You’ve only been gone for four days and you’ll be home in one. Get over it. The other part of me, the part that felt her tears on my shoulder and saw the weight of the world on hers, hugged her and let her cry. That part of me marveled at how much love was needed to cry over a person after being separated for only four days when you know you’ll see them in one.

Despite all evidence to the contrary, 13- and 14-year-olds love. They love hard. In the weeks that followed, I learned a few more things about teenagers. They (and I cannot stress this enough) cannot stay in two straight and manageable lines if their lives depend on it. They have this energy that comes from a never-depleting source that I have yet to discover. There’s laughter in all things, even when there shouldn’t be—especially when there shouldn’t be. The world is their kingdom to rule or destroy or enjoy. Musicians and athletes, students and teachers, artists and bakers and scriptorians. They’re everything and everywhere and believe they can fill the universe. How can you contain all of that in two orderly lines? You can’t. It explodes everywhere.

One boy in particular had trouble containing his energy. A constant, mischievous grin twisted under his banana snout, and his bleach-blonde hair looked like dynamite moments after detonation. He disturbed more lessons and games than we had time for and made it his mission to be the funniest person in the room—no matter the cost. That meant throwing berries during scripture study and stealing all of my reward candy and playing games on his phone at full volume while we waited for meetings to start.

I loved him. That’s all I could do. After five weeks, I’d learned to love just as hard as those 13- and 14-year-olds. As the week progressed, that explosion boy’s smile extended to a genuine one. On the last day, he crossed the dark, night grass and sheepishly lowered his head. And he said, “When I go home, I’m going to help my mom more because I love her.” And 13- and 14-year-olds are bad liars, because when they tell the truth, you can feel the weight of it.

Like that girl in New York. She wore self-ligating American brackets with purple bands. Her clothes always hung off her gangly arms in sharp angles. She had nuclear fusion going on under her skin. She glowed. She spilled over with energy. She was always the first to volunteer, the first to help, the first to answer questions, the first to dance or sing, no matter how many eyes were pressed on her.

After quiet time one night, she sat up in her chair and smiled.

“You know why I always raise my hand?” she asked.

“Why?” I’d thought she was just an overachiever, though a wonderful one.

“It’s not because I like to,” she said. She hugged herself in her ratty pajamas. “I get scared being in front of people. But I know that when I do scary things, they stop being scary after a while.” Light flowed off of her. “So, I make myself do scary things.”

The stuffy, humid heat coated my skin. The smell of old sweat hung heavy in the air. The bravest person in the world sat in front of me.

I think about them a lot. I stretch their names out across my head like a banner so I don’t forget. I keep their stories in my notebook, and I carry their tears on my shoulder. I watch the world spin and find comfort in knowing it doesn’t belong to me. It belongs to the 13- and 14-year-olds with electricity at their heels and so much love that it runs through them like a current.

The thing about borzois is that they’re beautiful. Their tails are long and curl in the golden ratio of perfection. They’re tall and lean and muscular. Fur soft and silky and ethereal. And there’s that long, glorious, awkward banana snout that gives you an unobstructed view to their eyes. Wide. Dark. Full of nothing but love and wonder.

I sometimes go back to the orthodontist’s office. I hear wires and sharp tools; smell the chemicals and hear the snap of gloves; see the borzois in the chair. When I catch a glimpse of their boundless eyes, I smile with my teeth.

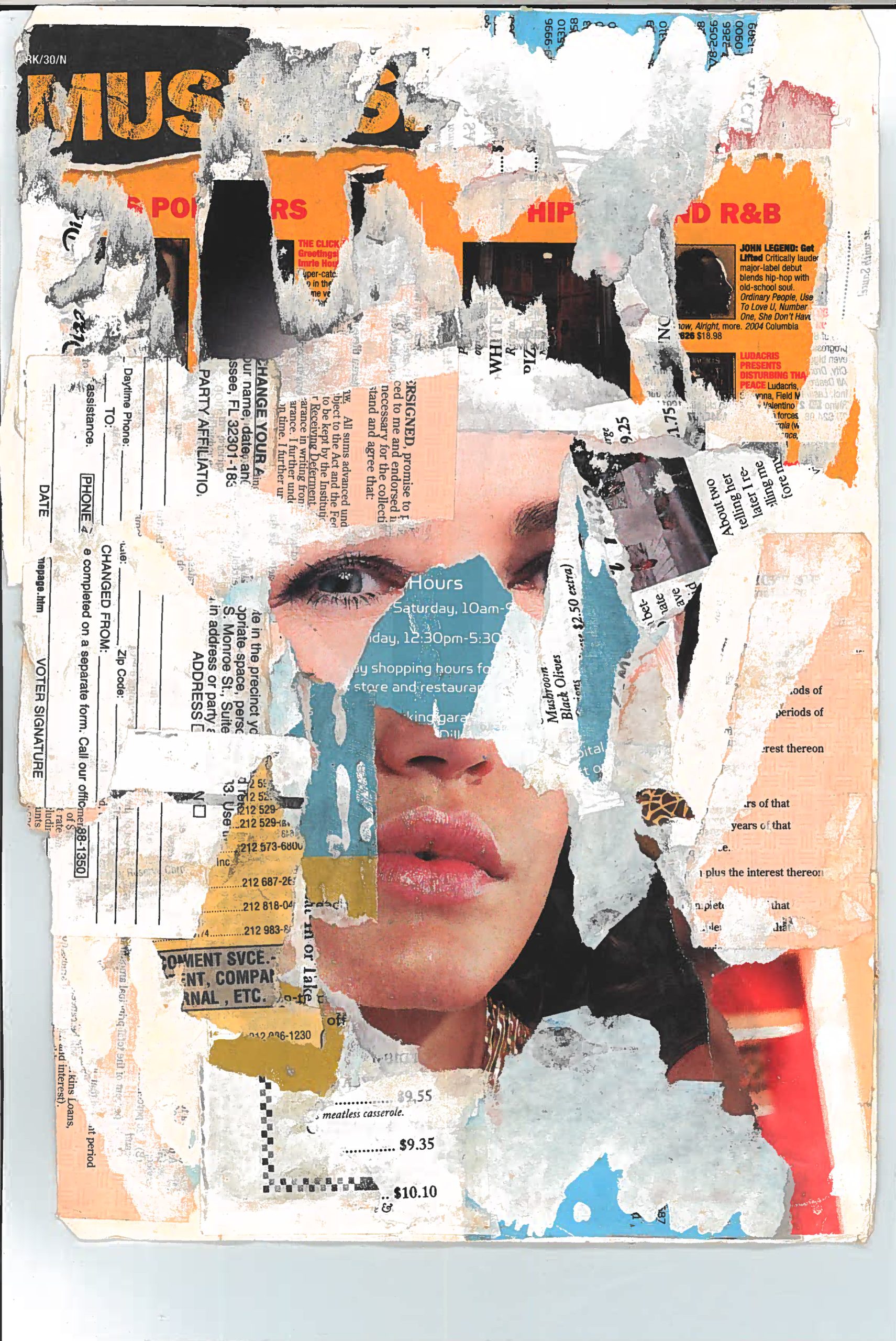

Header image by Shane Allison, Inscape Fall 2023