By Carly Quereto

I.

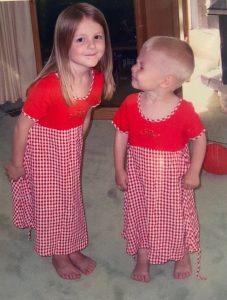

When I was five, I found two matching dresses packed away in a storage bin. I didn’t think to wonder then where they came from. My mother only had one daughter when I was five—she didn’t need two matching dresses. Even years later, when my sister Avery finally arrived, neither of the dresses were ever used, and my mom still doesn’t know why she had them. When I was five, I dressed me up in one and you in the other, your chubby arms not filling up the too-big sleeves. It pooled around your ankles. We played “Little Sisters.” I didn’t have any sisters at that point—just you and one Baby Brother. Mom beckoned, camera ready to snap a memory. I tried to get you to look at her, your cheesy face stayed looking up to me instead.

Maybe when I was five I needed you to dress up in a silly red-orangey dress so that Mom would snap a picture and I would have forever immortalized the truth that You Look Up To Me—not in a way that puts you beneath me, but in a way that says that I Exist, that I Make A Difference To At Least One Person. Maybe your belief in me makes me more than I am.

II.

Mom saves snapshots—that’s how I know we were best friends back then, as little kids. As we grew, gathering years and inches, I pestered you and you teased me, and we weren’t quite “best friends” anymore. Every two years a new Brother was born (and a sister Avery, five brothers down the line). Family meant busyness and bustle, and I’m ashamed to say that to me, you got lost in the shuffle for some years. You were just another of The Brothers. Teenagerhood brought a level of independence for both of us that somehow drew us back together.

When I was fifteen, you started coming with me to early-morning-Bible-study class. A year before you were old enough to, but, ever trying to prove yourself More Than You Are, you insisted and Mom conceded. I think that’s when our closeness started reviving. Soon, I couldn’t imagine how I ever went without you—I lived for our back-and-forth texts during class about how bizarre it was that the teacher had that much energy that early in the morning. What made even the early mornings enjoyable (for me, who never enjoys early mornings) was when you started getting up even earlier than necessary to creep upstairs, warm up a pot of milk, and concoct from scratch the richest, most indulgent hot chocolate—cocoa powder, raw honey, and a splash of vanilla extract, topped with cinnamon. Simple—I tried assembling it on my own sometimes—but somehow it always tasted better when you made it, sneaking around in the dark before dawn. You would hand me my thermos as we got out of the car, and it would take half of the class period for it to cool down enough to sip.

Maybe when I was fifteen I needed you to come with me to early-morning Bible study because without your made-from-scratch cocoa I wouldn’t have stayed awake long enough to learn anything.

III.

When I was sixteen, six of The Brothers and Avery had joined us. I played taxi driver for our busy mama, and the old family minivan—affectionately dubbed “The Duchess”—came into my custody. You started relying on me (rather than Mom or Dad) to get around town, and you and I found new late-night freedom. There were pitifully few places open late, even though we lived in a college town. That was okay—we only needed one. I remember nights upon nights of quick trips to the pale-pink-painted cookie shop, there-and-back-again with our treasure.

When I was seventeen, we read Harry Potter at the same time. I trekked down to the neighbors’ house to borrow the books, one volume at a time. You took them over as soon as I was done and cruised the chapters before I took each one back to the neighbors and returned with the next. We discussed them after The Brothers (seven of them now) and Avery were asleep. The bathroom between our bedrooms spilled golden light into the hallway and illuminated our late-night chats. We talked about how Harry was the most one-dimensional main character we have ever read. We mutually decided that the real villain of the story was Albus Dumbledore, not Voldemort.

Maybe when I was seventeen I needed you to read Harry Potter with me and talk about the books with me in the glow of the bathroom light that spilled into the hallway so that I could learn to read between the lines, understand what wasn’t written.

IV.

We talked about a lot of things in the golden glow of the bathroom light, sprawled out on our stomachs on the hallway carpet. That was our home base, from when we first started becoming friends again, at fifteen, until I grew up faster than you did and moved away. That space anchored me at the end of every day.

Okay, I confess. Maybe not every day. Like brothers and sisters do we bickered, and sometimes the bathroom light was switched off by either you or me—the understood signal of I’m Not Happy With You Tonight. But those memories have faded. Even now, I wish there was a patch of golden-lighted carpet where I could return, where you’d be waiting with wisdom.

We would whisper because if Mom heard us, she’d feel the need to come downstairs. She wouldn’t yell at us or anything, but as the oldest siblings of seven—then eight, then nine—we both felt a keen sensitivity to the overworked-ness of our mama and wanted her to sleep when she could. Still, despite our efforts, sometimes our discussions launched us into noisy giggle fits as we imagined up the comic—the entertainment that only we two understood.

Once, I got you to admit which dark-haired, dark-eyed, beautifully joyful girl had caught your still-little-boy heart. You shoved my hand away as I rustled your hair—your ears flushing as orangey-red as the dresses of our childhood make believe, and for a flash of a second I thought you were Growing Up Too Fast, and I wished for bygone days.

Often, you brought a blue-backed book of scripture; we flipped the slippery-thin pages and discussed God.

Oftener still, we discussed the solemn in those golden and black hallway nights. Back and forth, we swapped opinions on the disagreements between our friends, the ways we saw micro bullying among them or among The Brothers and Avery. We shared ideas, how to mend breaches. We counseled about our parents, feeling a care for them more characteristic of parent-for-child than vice versa. You were always more sensitive to the warning signs that Mom was wearing thin—I needed your insight on her sometimes.

Maybe I needed you in those hallway-bathroom-light talks to understand how to love The Brothers and Mom the best that I could.

V.

You turned sixteen just three months after I turned eighteen. After considerable encouragement from myself and Mom, you reluctantly agreed to ask a girl to prom—your first date ever—and joined me and my group of friends going.

Had I not been going, you wouldn’t have. You needed me alongside you on this leap of faith into the unknown.

We piled into a friend’s car after leaving The Duchess at a friend’s house. Your date sat between you and me in the back seat. I thought you looked dashing—buttoned and starched and cologned up—and your date thought so too. She playfully flirted with you, and I could tell that you were swimming in deep waters, floundering for words to say back. I watched, silently rooting for you in your steps outside your comfort zone. The tips of your ears were red all night and you hardly said a word.

After the dance, we dropped off our prom dates, picked up The Duchess, and you breathed a massive sigh of relief. Off came your tie, and off melted your nervousness, in record time. You could take your tie off with me—take off the pretense of Having It All Together.

As I put Her Grace in gear, we made eye contact across the LED lit dash and both knew that we had one more stop to make before home. The familiar pale-pink-painted late-night cookie shop welcomed us with a glow that leaked out into the parking lot. We two, we lived our own secret life in the dark hours.

Maybe when I was eighteen I needed you to come to prom with me so that I didn’t get so lost in trying to be so pretty for a boy that didn’t matter that I forgot what really did—cookies after dark with my brother.

VI.

Your silence that prom night was uncharacteristic. You have always been very outspoken. You learned to be so over the years of being the shortest, smallest, skinniest boy of your age. You learned to compensate for your diminutive stature with intellectual prowess and a cocky demeanor that comes across almost like a chip on your shoulder. Do you remember the day that you decided to become a Swearing Man? You must have been seventeen, making me nineteen, just before I left home. You spent the afternoon cursing like a sailor, unabashed in front of me, Mom, The Brothers, Avery, Dad, The World. Though always bold in your speech, cursing had never before been your thing. But I think that sometimes your big personality just couldn’t be contained anymore in your little body, and on that day it just exploded out. Mom was so shocked when you became a Swearing Man that she could do nothing but let you. I thought it was hilarious and secretly admired your barefaced pluck. After a few hours, you resolved that you’d had enough and dropped the profanity from your vernacular. Except, sometimes it sneaks back in, but only with me.

You took up the space with your mind and voice that you didn’t with your body. You tried to not let people see that their comments about your size chipped away at your confidence—but me, I saw it.

Maybe when I was nineteen I needed you to become a Swearing Man—just for a day—just to show me that some rules need to be broken, just so that I know that they can be.

VII.

The Duchess accompanied us on our twice-a-week trips to the library for math tutoring. The eleven-minute drive took us through a playlist of songs that made us laugh, head bang, and belt—but only you and me. These songs didn’t mean anything to me when listened to in the company of anyone else. It was our shared soul soundtrack:

Sing, by Pentatonix

Magic, by B.o.B. (feat. Rivers Cuomo)

Jesus Is a Friend of Mine, by Sonseed

For What It’s Worth, by Buffalo Springfield

The Sound of Silence, cover by Anna Kendrick from the movie Trolls

Who knows how we came into possession of this eclectic collection of songs. Even now when I hear any of them randomly, they take me back to those eleven-minute drives in The Duchess on the way to the library. They are, always and forever, the Library Songs, amen.

Maybe when I was eighteen I needed you to sing in the car with me on the way to the library every week because if you didn’t, I would have given up on finding joy in the in-between moments.

VIII.

There are things I know about you that don’t connect to anything else, except that they’re you, and that must mean that they matter, somehow.

You hate mayonnaise; you’ll never eat it on a sandwich or anything else.

You like your hair longer on top and shorter on the sides so you can comb it into a big swoosh above your forehead. We—the family—call it your pompadour.

You always dress with class—not looking for attention, but respect.

You can take apart any bicycle and put it back together in better condition than before.

You drove a green Ford Mustang in high school that you bought secondhand with the cash you saved from fixing bikes. You let me drive it, once. You planned on selling it for a profit but then the COVID-19 pandemic hit and nobody was buying Ford Mustangs so Dad bought it from you.

So many things you did, I did first—church camp, out-of-country humanitarian trips, learning to drive, growing up and leaving home.

Maybe you need me. Maybe, if it weren’t for me, there wouldn’t be footsteps for you to follow.

IX.

When I was nineteen, I was grown up and making plans and catching flights. I was headed across the country to live on my own, volunteering on a church mission. I wouldn’t see you for eighteen months, except for an occasional Sunday-night video call. Some of The Brothers, Avery, Mom, and Dad were packed in the family van (we called her the Big Rig—she replaced The Duchess after I got her into an accident) to accompany me to the airport. You had volunteered to stay at home with The Baby Brother. In the whirlwind of leaving, in the back of my head, I wished I could tell you to come, to not say goodbye just yet. But the plane was on the tarmac and We Have To Leave Now, said Dad. I clicked my seatbelt and turned to look one last time at the home I was leaving. Here you came, rushing down the front porch steps, Baby Brother in arms, no shoes. You launched into the backseat, just as Dad put the van in reverse. From inside the house, you must’ve read my mind that was pleading for you to come.

At the airport, we all nine clustered together for Mom to snap another memory. Me and The Brothers and Avery in the parking garage of the airport, and you, with no shoes.

Maybe when I was nineteen I needed you to come to the airport with me because if you didn’t I wouldn’t have believed in myself enough to get on that plane.

You moved to Africa for your own missionary service before I got home.

X.

You were in Africa the entire year I was twenty.

XI.

I’m twenty-one now. I’ve moved back to my hometown, reunited with The Brothers and Avery and Mom and Dad and started going to college. You’re still in Africa.

I’m twenty-one and I’ve met a Hawaiian Boy who takes me on dates and makes me food and listens to my dreams. He doesn’t know you. Mom and Dad like him.

I’m twenty-one and I’ve fallen in love with the Hawaiian Boy. You would like him, I think. I mean, he’s not into sports or bikes or cars like you are, but he’ll talk about literature—Rowling, yes, but also Tolkien and Hugo and Shelley and Shakespeare and Vietnam War stories—and movies for hours, like you and I used to. I spend my Sunday nights with him, watching the way he lives and laughs and makes hot chocolate differently than you do. Often, I find myself remembering that my Hawaiian Boy doesn’t know you—how could that be? You, who spent day after day, and, more importantly, night after night with me—the nights of the heights of our young lives. You, who were with me when I learned to drive and to dance and to dissect stories. You, who taught me how to change a bike tire and read Mom’s moods. You, who I consider to be as much a part of me as my own soul—how can this Hawaiian Boy know me if he doesn’t know you?

I haven’t seen you without the barrier of a screen since the barefoot day in the airport. On the occasional Sunday night that you call me I sequester myself away from the bustle of brownie-making and busy friends to listen to your faraway voice. You tell me that it’s still Hot and Sticky in Africa. Tell me how you’re doing your best to get along with your roommate. Tell me how you’re nervous about coming home. You’ve built a life in the Hot and Stickiness, and you’re apprehensive about being uprooted again, trying to build a new life again when you come home to go to college.

You need me to tell you that It’ll Be All Right, that You Got This.

I try my best.

When you call me on Sunday nights my Hawaiian Boy is with me sometimes. I introduce you through the screen, you become friends, somewhat. I want you to like him. You ask him what he’s studying in school, what he likes to do, how he learned to speak Mandarin. He asks you about Africa, about your adventures, about your goals and dreams.

You tell him how you’re nervous about coming home. How you look at me—married, going to school, working a job—and you think that I’ve got life all figured out.

I’ve handed my phone off to my Hawaiian Boy, now only his face fills the screen but from my corner of the couch I can hear your voice coming from across the world. I listen—wondering at the way you don’t see your own potential the way I see it. I wonder at your nearsightedness to think that I have some kind of preparation that you don’t have—that we didn’t somehow spend the most formative years of our lives growing side-by-side, roots intertwined, reaching towards infinity together. I wonder that you—you, my brother who can do it all—have somehow made your infinity unreachable in your mind.

But my Hawaiian Boy doesn’t wonder. He knows your nervousness in a way that I can’t know, I think. A knowing between brothers. He remembers what it was like in his own growing up to come home from living in Asia and start going to college and feel like nothing was figured out. He can see your future—he’s lived it—and he believes in you as much as I do.

You start to ask him for advice—about college, about part-time-jobs, about dating, about growing up. I listen.

When you come home you’ll be twenty. You’ll get an apartment of your own and a job of your own and buy groceries on your own and attend college on your own—the same college that I’m attending, but you’ll do it on your own. You’ll get your own wheels to drive around town, won’t need me to take you. You’ll have roommates and friends to go on late night adventures with. You’ll be in school studying how to build bikes and cars, or maybe businesses—pursuing dreams I have never dreamed. You’ll ask for advice from others, maybe my Hawaiian Boy, maybe not me. When you’re twenty, will you need me at all?

I don’t really need you like you needed me back in high school to get around town, riding shotgun in The Duchess. But maybe, even though I’m grown up, I still need you like you needed me to go to prom with you. Simply having a familiar soul in the passenger seat—one who sees the best in me and believes that I can do anything, anything. Maybe that will make the world of grown-ups easier to navigate.

Maybe, now that I’m twenty-one, I still need to know that I Exist, that I Make A Difference To At Least One Person.

XII.

When you’re twenty and you come home, I’m afraid you won’t need me anymore but that I’ll need you more than ever.

Carly is currently a BYU student studying creative writing at BYU. She loves her husband and baby, crocheting, and chocolate peanut butter ice cream. She dreams of someday writing a book.