By Sarah Safsten

Content Warning: This essay contains a frank discussion of suicide that might be difficult for some to read

John Keats once wrote that melancholy and beauty dwell together. He certainly seems qualified to make that assertion—he suffered the deaths of his close family members, desperate financial straits, career difficulty, bouts of depression, and a fatal case of tuberculosis yet still managed to write some of the most sublime poetry in the English language. In his “Ode on Melancholy” (1819), he describes the eponymous emotion as a sudden, unavoidable rain shower. Yet Keats warns readers to resist the temptation to seek for relief through poisonous Wolf’s-bane or yew-berries, claiming that “in the very temple of Delight / Veil’d Melancholy has her sovran shrine.” While this may be a poetically pleasing paradox, it has been my experience that the balance between melancholy and beauty is not an equal one—the two occasionally show up together, but in terms of quantity, the scale often tips toward melancholy.

*****

There have been times when I loved being alive. I adore the sharp, chilly smell of damp earth, fallen leaves, and coming rain on autumn mornings. I relish the coolness of the sprinklers on my bare legs during summer evening runs. I delight in inventing dance moves with my husband in our kitchen. I remember the uncomplicated joy I felt when I played in the backyard with our family’s Springer Spaniel, Jack, for the first time. Once, on my fifth birthday, my dad and I went out for an adventure at the farm where he worked. We drove around in a golf cart, chasing the geese and laughing when the flock waddled away from us in a flustered flurry of feathers. Then we went down to the riverbank. We each picked up the biggest rock we could find and hurled it as far as we could. Our noses were red, and our breath came out in misty clouds in the January Colorado air. That was before my parents divorced, so my dad and I came home to a warm house, my mom making rolls in the shape of an “S” for my name. I was blissfully unaware of the strife within my parents’ relationship; I felt secure and unworried.

There have also been times when I wished I wasn’t alive. No, I haven’t always kept a mental list of the top five best ways to kill myself. But recently, every waking moment (and every dream) has been clouded with a lingering, sticky melancholy that I can’t wash off, cut out, or ignore. Depression is an apt name for this feeling—a crushing pain that pushes me downward—squeezing, strangling, suffocating. Even on happy days, like birthdays and Christmas, depression dulls the excitement and makes me feel distant and invisible, separated from the rest of the world by a one-way mirror. The pure delight of my childhood adventures seems fragile and far away. Autumn mornings, summer sprinklers, and kitchen dances aren’t enough to balance out the despair I feel so often.

*****

Hippocrates, one of the earliest physicians who recognized depression as an illness, theorized that the human body was composed of four humors: black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm. He believed that melancholia was the result of an imbalance of these four caused by an excess of black bile. Hippocrates suggested various treatments, such as bloodletting, with the goal of removing the excess. He postulated, “Extreme remedies are very appropriate for extreme diseases.” While I don’t believe this statement is true—extreme remedies often exacerbate the damage done by extreme diseases—Hippocrates’s logic can be appealing. At times, I wish for a remedy as extreme as the depths of my sadness.

Fortunately for me (and modern medicine), doctors have now stopped prescribing bloodletting. Ironically, many who silently struggle with depression still resort to antiquated methods—to a type of self-medicated bloodletting, or self-harm, in search of relief from emotional pain. In my case, I started cutting when I was serving as a full-time missionary in South Korea. Almost a year into my mission, the rigorous daily schedule of proselyting with a difficult companion started to exhaust my body and torment my mind. The depression, fear, and anxiety had spread throughout my whole body. I was swollen with pain and began to see the razor-sharp blade on my pocketknife as a tool that could not only open boxes but also distract me from my seemingly unsolvable problems.

For two months, I imagined what it would be like to cut myself, to slice my skin open, to bleed. I yearned to translate the extremity of my sadness into physical action. I thought that cutting could express the emotional pain inside me, pain which could not be fully communicated through language, both because my companion did not speak English, and because all the words in both the English and Korean languages could not accurately explain the despair I felt. Sometimes I opened my pocketknife and pressed the blade against my skin but stopped before it made a mark. I wasn’t afraid of the pain—I was afraid of the judgement of my excessively cheery companion and the punishment of my strict mission leaders.

For a while, I drew with a ballpoint pen on my wrist the designs I wanted to make with the blade of my knife, fantasizing that my emotional pain could escape through the openings of my flesh. During the humid, fish-scented summer, my companion and I struggled to find people to talk to—only a brave few dared to brave the heat outside, and hardly anyone wanted to let a pair of sweaty strangers into their homes to chat about a god in whom they did not believe. We filled our time by walking up and down the beachfront. My companion talked about her favorite Korean TV dramas and unsuccessfully tried to teach herself to whistle. I flipped a pen back and forth between my fingers, dreaming of emotional relief. When I was especially anxious or panicked, I dug the point of the pen into my skin as hard as I could, creating layers and layers of dark ink marks on my wrist, which I later tried to scrub off in the bathroom sink of our studio apartment. Drawing lines on my wrist was never as cathartic as I hoped. I always wished I had the courage to use my knife.

About six weeks later, my mind was overloaded with hate toward myself. My overgrown pixie haircut had grown limp and frizzy in the muggy Korean summer. I started losing large patches of hair and gaining weight from stress. Of course, binge-eating the American candy sent to me by my family didn’t relieve my stress, and it didn’t help my looks that I didn’t comb my hair or iron my clothes. Several of my companions noticed my frazzled appearance and often cited it as the cause for our lack of proselyting success. My weaknesses, faults, and inadequacies frenzied my mind until I felt that my blood was turning into the black bile Hippocrates described. I was the only American within a fifty-mile radius. Each morning, we sprinted to the bus stop to clamber aboard a belching hellhound of a bus that lurched into traffic before we could get securely inside. All afternoon, we walked past blocks and blocks of fifty-gallon fish tanks filled with ribbons of eels slithering around each other. Hungry customers would pull one out with a large pair of tweezers and roast it alive over a bed of coals next to the tank. Other vendors at the market sold crabs as big as my torso, live squid, and huge metal tubs filled with beondegi: shivering silkworm pupae served in paper cups with toothpicks. I felt incredibly isolated and uncomfortably foreign in my physical surroundings, as well as in my own body.

In one of those moments of acute depression, while my companion was in the bathroom, I dug my pocketknife out from the bottom of my suitcase and pressed the razor-sharp blade against my skin. Almost without thinking, I scratched swollen bloody lines into my wrist. At first cautiously, then roughly and angrily, I sliced my skin over and over again. I was careful to cut just deep enough to draw blood but not enough to warrant stitches. Contrary to Hippocrates’s theory, cutting didn’t bring balance to the humors in my body. But in some twisted way, cutting helped by presenting me with a problem that I could control—the pain of my bleeding skin—which was easier to solve than the problems presented by my missionary work.

*****

Depression as a mental illness was initially labeled melancholia. Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (first published in 1621) is one of the earliest texts we have that scientifically analyzes depression. Burton suffered with depression from an early age. In part, his motivation in writing his treatise on melancholia may have been to find a cure for his own sadness. Although Burton’s scientific explanation of depression was somewhat primitive, his description of depression resonates with me. In a poem, he complained, “My pain’s past cure, another hell, / I may not in this torment dwell! / Now desperate I hate my life, / Lend me a halter or a knife; / All my griefs to this are jolly, / Naught so damn’d as melancholy.” What “jolly griefs” was Burton referring to when he wrote this? Stale bread for lunch? A stubbed toe? Walking under a balcony right when his neighbor emptied their chamber pot? Regardless of what the daily annoyances of life in the seventeenth century were, I can empathize with Burton’s longing for a knife.

Any of my external griefs—poor scores on an exam, offensive Facebook posts by ignorant people, arguments with my family—are jolly compared to the pervasive, heart-squeezing melancholy. Depression spreads through the veins like poison, enraging some and numbing others, leaving wilted and shriveled emotional molecules in its wake. Because there is often no circumstantial cause of depression, it is difficult to cure. It can’t be fixed with Cheetos, positive affirmations, nor with the well-meaning but maddeningly useless words, “Let me know if you need anything,” “It’s going to be okay,” and “Try to be positive.” People who do not comprehend this fact are prone to telling their depressed friends to buy some running shoes and go for a jog. They say, “The endorphins will cure you!” My life would certainly be much easier if this were true, but melancholia does not back down so easily. Thoughtless repetitions of trite aphorisms can make those who suffer from depression feel mocked, isolated, and misunderstood. It is more benevolent and compassionate to accept the incurable reality of depression than to hand out the useless Band-Aids™ of cliché consolations. Perhaps like me, Burton had to hold himself back from strangling clueless people such as these.

*****

I was eventually medically released from missionary work because of depression. The fact of my going home “early” tortured me. I felt ashamed and humiliated. I was the first child in my family to serve a mission and the first one who didn’t have what it took to serve the whole time. I knew I was depressed. I knew that self-harming was problematic. During my mission, and at the moment I write this, I felt that I could keep pushing until the end—I had fewer than six months before I would be officially released. Nevertheless, the choice was not mine to make; once my mission president and mission doctors found out that I cut myself, they told me that I would be going back to America on the first available flight.

Before I got on the plane to come home, I said a prayer. I started by telling God I was sorry for being depressed. Sorry for failing Him. Sorry I couldn’t stay in Korea longer. As I apologized, He interrupted my thoughts with a warm, reassuring feeling: “I love you more than I love your mission.” And for a moment, my thoughts and fears quieted enough to hope that, someday, I might recover. The voice that hushed my apology and assured me that my service was acceptable comforted me. But my heart still ached because I doubted what I had felt and did not accept my own service. It was not enough for me.

I grew up believing that I owed God everything—that my life was not my own and that the one real gift I could give Him, through missionary service, was my time and my free will. Before I submitted my paperwork, I didn’t like the idea of missionary work. I wasn’t enthusiastic about tracking down strangers on the street to tell them to repent. In spite of this (or perhaps because of this), I thought that my sacrifice in going would be counted even greater and therefore would be more valuable to God. I believed that it would take a heroic feat of Herculean stature to reach God and get Him to take away my depression. Ironically, my dream of becoming the perfect, consecrated missionary was the blueprint for my own Tower of Babel—an illogical, impossible formula for success.

To me, my early return from my mission signified that I had not only failed my Heavenly Father, but I had failed myself by breaking my promise of being the perfect missionary. For months, I thought that this failure devalued my entire existence, and I wanted to die. At the time, I knew mentally but could not kinesthetically, physically, or emotionally accept my Heavenly Father’s spiritual reassurances that I was enough and that my mission was acceptable. In my distorted narrative, the fact that my mission ended early prophesied God’s eternal disappointment in me. Coming home was the death of my dream of being the perfect consecrated missionary, which death hurt far more than the depression or the bloody cuts on my wrist.

*****

A few weeks after I got home from Korea, I was driving home late at night. I hurtled down the freeway at ninety miles per hour and thought, more than once, “I could jerk the wheel and crash into the median next to me—I could just end it all in an instant. Or I could just as easily pull out the sharpest pocketknife in my dresser drawer and slash my wrists and arteries, this time inflicting enough damage to end the depression permanently. It would be as simple as cutting a piece of twine or slashing open a letter. Swallowing all the leftover codeine in my medicine cabinet could work pretty well too.” Winston Churchill wrote of the difficulty of resisting a similar suicidal impulse: “I don’t like standing near the edge of a platform when an express train is passing through. I like to stand back and, if possible, get a pillar between me and the train. I don’t like to stand by the side of a ship and look down into the water. A second’s action would end everything. A few drops of desperation.”

Churchill spoke of his own struggles with melancholia through the metaphor of a black dog that must be kept on a leash. His secretary, John Coleville, wrote,

Of course we all have moments of depression, especially after breakfast. It was then that Lord Moran [Churchill’s doctor] would sometimes call to take his patient’s pulse and hope to make a note of what was happening in the wide world. Churchill, not especially pleased to see any visitor at such an hour, might excuse a certain early morning surliness by saying, ‘I have got a black dog on my back today.’

For the rest of the day, Churchill stood back from the trains. But unlike the pillar of safety that stood between Churchill and the rushing train, separating him from the fatal consequence of desperation, this concrete median tempted me with the dangerous accessibility of death. So many options for relief.

I’ve been home for over three years. I’m married to Robert, the love of my life, who never makes me feel judged or embarrassed for being depressed. He has never once said a disparaging comment about my early return from my mission or my frequent breakdowns. Yet I still have to hold tight to the steering wheel when I drive to keep myself from breaking through the barrier—waiting for a truck to smash my car and turn me into roadkill.

*****

Living with depression and fighting off suicidal thoughts every day is an arduous struggle. But for all the people who, for whatever reason, don’t understand me or my depression, there are plenty whose kindness surprises me and makes my sadness seem less suffocating. One night, when I was feeling especially depressed, I visited my best friend Bethany. We had both been home from our missions for about two years, and she was just a few days away from getting married. When I walked into her apartment, I saw, instead of Bethany, a petite Chinese woman standing next to a small table filled with essential oils and herbal teas. Bethany explained by telling me that her soon-to-be mother-in-law (her English name is Grace) had flown in from China and was staying with her until her wedding. Through her digital translator, Grace told me that I looked tired and offered to treat my sore muscles with some of her essential oils. She directed me to remove my clothing and lie on her bed.

In my nakedness, I felt vulnerable and exposed, but I trusted Bethany without question, and I trusted Grace by association, so I did as she asked. Grace lined up twenty bottles of different essential oils on the table and, one by one, rubbed them into my skin and my scalp. Her hands were small but strong and found each of my pressure points with ease. The deliberate, rhythmic movements of Grace’s hands on my skin relaxed my muscles, relieved the anxiety I felt in that moment, and made me feel safe, taken care of. I was touched that a total stranger was willing to do what she could to ease my pain, even though she had no obligation to me. Grace was not offended by my nakedness or my strangeness to her.

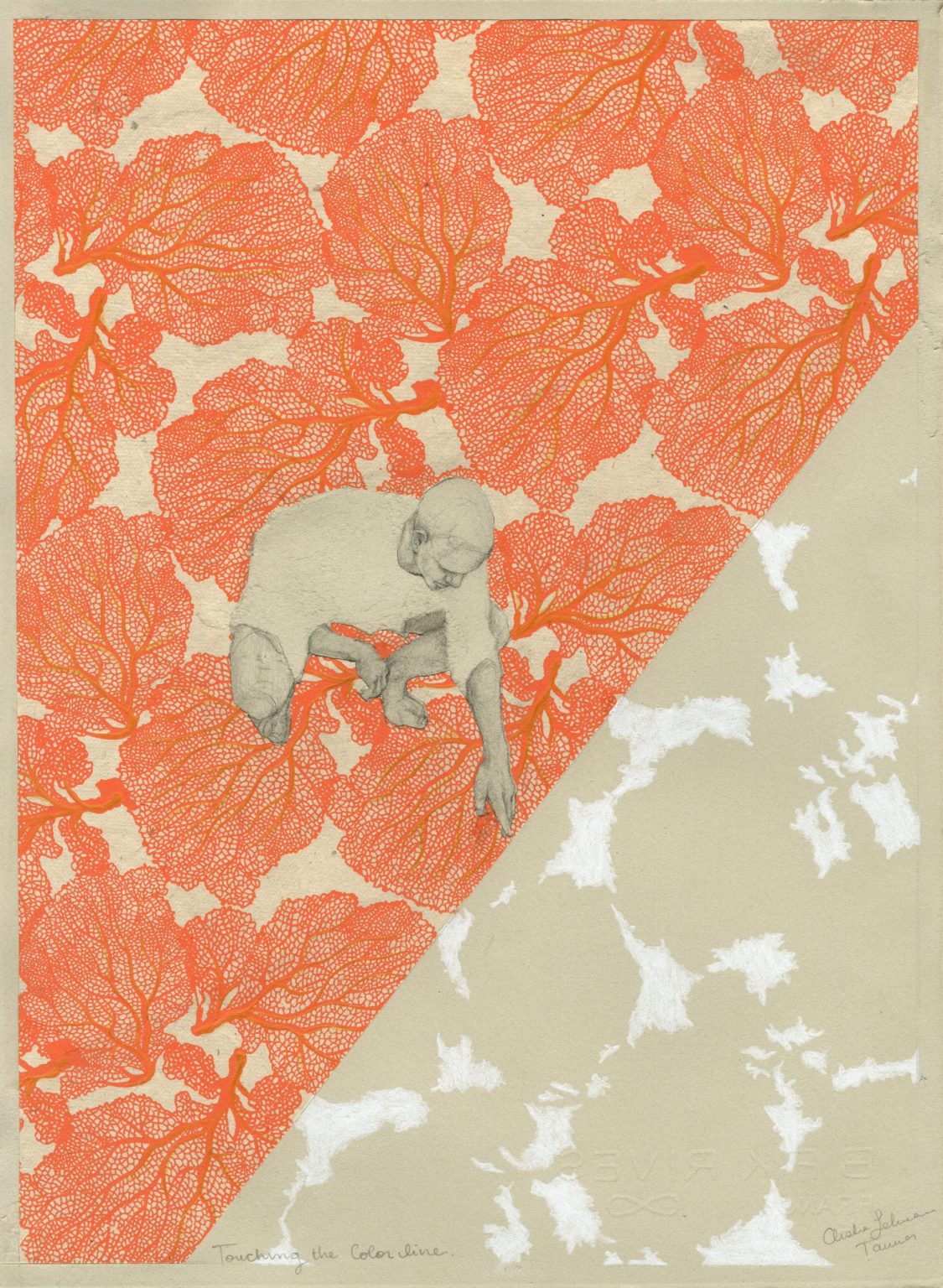

I am afraid of vulnerability because exposing myself to others often invites judgement and criticism. But Grace’s massage showed me that risking physical and emotional nakedness can be an opportunity to find the beauty within melancholy moments, which often stems from interpersonal connection. Paul once wrote to the Hebrews: “. . . all things are naked and opened unto the eyes of him with whom we have to do. . . . For we have not an high priest which cannot be touched with the feeling of our infirmities; but was in all points tempted [and afflicted] like as we are, yet without sin.” Believing that Jesus physically experienced the depths of my depression comforts me. It allows me to put aside my shame and lay my naked soul before Him. When I do so, He anoints me with his love, as Grace did. Nakedness is a necessary precursor to healing.

*****

The American poet Sylvia Plath characterized her despair through the metaphor of “a great muscular owl . . . sitting on [her] chest, its talons clenching and constricting [her] heart.” At other times, Plath’s mental illness presented itself in the form of numbness, which she described in her semi-autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar: “I felt very still and very empty, the way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle of the surrounding hullabaloo.” Plath tried several times to take her own life, once by overdosing on pills and once by driving her car off the side of the road into a river. A few months after The Bell Jar was published, Plath put her head into her oven and killed herself through carbon monoxide poisoning.

A few months ago, I too felt like the “eye of a tornado” amidst “the surrounding hullabaloo.” This feeling intensified to the point where I had to go to the hospital because I planned to kill myself, even setting an ideal time and place. I called my husband Robert and asked him to drive me to the ER. While I believe I made the right decision, I remain irritated about my experience with the ER doctors that night. After going through their obligatory list of questions and having me sign a suicide safety plan, the social worker made me promise not to kill myself and to go home. His job was done—the hospital wasn’t responsible for me. In my journal that night, I wrote, “Next time I’ll save myself my $500 deductible. Instead, I’ll just lock myself at home in a padded room, go crazy, climb the walls, and scratch my eyes out.” I didn’t expect my visit to the ER to cure my depression, but I had hoped to come away from the experience feeling less suicidal than when I came. That didn’t happen. Instead, I learned that I am the primary force keeping myself alive. Doctors, psychiatrists, social workers, even my emergency contacts listed on my safety plan could not hide from me the diverse opportunities I had to kill myself. In the end, my life was my own responsibility. I continued to move dully along through the “surrounding hullabaloo.”

*****

While a prisoner in the jail at Liberty, Missouri in March of 1839, Joseph Smith felt abandoned by God. His diligent efforts to serve God were rewarded with several months in a cold jail cell. All his petitions and appeals to executive officers and the judiciary failed. In one dark moment, he prayed, “O God, where art thou? And where is the pavilion that covereth thy hiding place?”

Sometimes, like Joseph Smith, I feel like I’m screaming into darkness. One night, I lay curled in my bed in our six hundred-square-foot apartment. Robert came in, sat on the edge of the bed, and asked me what was wrong. Through my tears, I told him my doubts about prayer and the existence of God. “If He’s not even real, what’s the point of all this misery?” I cried. I thought Robert would respond by sharing his convictions about the reality of God and the importance of daily prayer. I expected him to ask me when my last appointment with my counselor was and if I had taken my medication that morning. But he surprised me by confessing that he too had his doubts. He lay next to me, held my hands, and joined me in shedding tears over our seemingly pointless suffering. I fell asleep with the weight of Robert’s arms around me, heavy and muscular from his construction labor job, confident in his love and in the sweetness of our shared melancholy.

Eventually, in response to his anguished prayer, Joseph Smith felt God reply to him: “My son, peace be unto thy soul; thine adversity and thine afflictions shall be but a small moment; And then, if thou endure it well, God shall exalt thee on high.” I’m still waiting and hoping for such peace in my own future, but I am grateful that my depression has given me opportunities to feel God’s grace and compassion, like Joseph’s did.

*****

I used to hope for total freedom from depression. I imagined that someday it would dry up and go away completely. I thought I could choose to get over it through my spirituality and reliance on God. But freedom didn’t come from waiting it out like a high school phase. It didn’t come from my obedience as a missionary. It didn’t come from medication, doctor’s visits, or a trip to the ER. It didn’t come even when I married someone who cared so deeply for me. I don’t believe I will find complete freedom from melancholia. Depression isn’t something I can escape from, but it is something I can learn to live with. Depression, even though excruciatingly difficult, is not fatal. Depression, even though ugly, chronic, and confusing, is not a sin.

Now, I’m less naive about the nature of my depression, but I struggle with finding balance between acceptance of my situation and hope for future healing. I take comfort in God’s promise, recorded by the pen of Isaiah, that those who “wait upon the Lord” will someday “renew their strength,” physically, emotionally, and spiritually. As I wait, I’m learning that healing is not a linear process. Some days, I find myself smiling and am surprised to find that the black dog of depression has temporarily lifted one foot from my chest. Other days, I can barely get out of bed.

For me, as for Keats, melancholy and beauty dwell together, but melancholy is often more obvious and I feel it more heavily. But even if the emotional scales tip heavily toward melancholy, I have hope that balance is possible. I think I’ve seen it—in God revealing Himself to me in the airport, in Grace anointing me with oils, in Robert sharing tears with me in the darkness. In the choice to stay alive for another day.