Hasanthika Sirisena’s work has been anthologized in This is the Place (Seal Press, 2017), in Every Day People: The Color of Life (Atria Books, 2018), and twice named a notable story by Best American Short Stories. She is currently faculty at the Vermont College of Fine Arts and Susquehanna University. Her books include the short story collection The Other One (University of Massachusetts Press, 2016) and the forthcoming essay collection Dark Tourist (Mad Creek Books/Ohio State University, 2021).

Interviewed by Fleur Van Woerkom

Inscape Journal: What was your first genre, fiction or nonfiction? Is there one genre that you prefer now?

Hasanthika Sirisena: It was fiction actually. I started out writing short stories, and I think for a long time that’s all I imagined myself doing. I think it isn’t a matter of what I prefer, but what are the subjects I want to write about, and what genre seems the most appropriate for the subject. I think my work uses fictional techniques, so I don’t really feel as if I’ve ever really left fiction, even though what I’m working on is true.

IJ: You have two pieces, “Unicorn” and “Confessions of a Dark Tourist,” that overlap. Which one did you write first, and how did you decide to incorporate parts of it in the other piece?

HS: I wrote “Unicorn” first, and I think that’s when I really started to wonder about writing something so serious as a work of fiction. I think one of the things that I couldn’t get across in the fiction so well, but that I felt nonfiction allowed me to do a much better job of, was to really address my own responsibility. I mean, you could read “Unicorn” and you don’t need to know that the writer took part in a war tour; you could think I just made that up completely, right? And so, you would be absolutely forgiven to think none of it was real, and it was all a figment of my imagination. But, when I wrote “Confessions of a Dark Tourist,” I had to own that I did this thing, that I had participated in something, and I thought that was very important. I wanted people to know this really happened, and I probably shouldn’t have been there. I would do it again, but I also think it capitalizes off a lot of people’s extraordinary pain, something that I had never experienced. I think contending with that is actually part of art so for me that’s a really great example. I like the short story “Unicorn” just fine, and people tell me all the time that it’s one of their favorite stories in the collection, but I really felt that I couldn’t let that be the only version of that particular encounter.

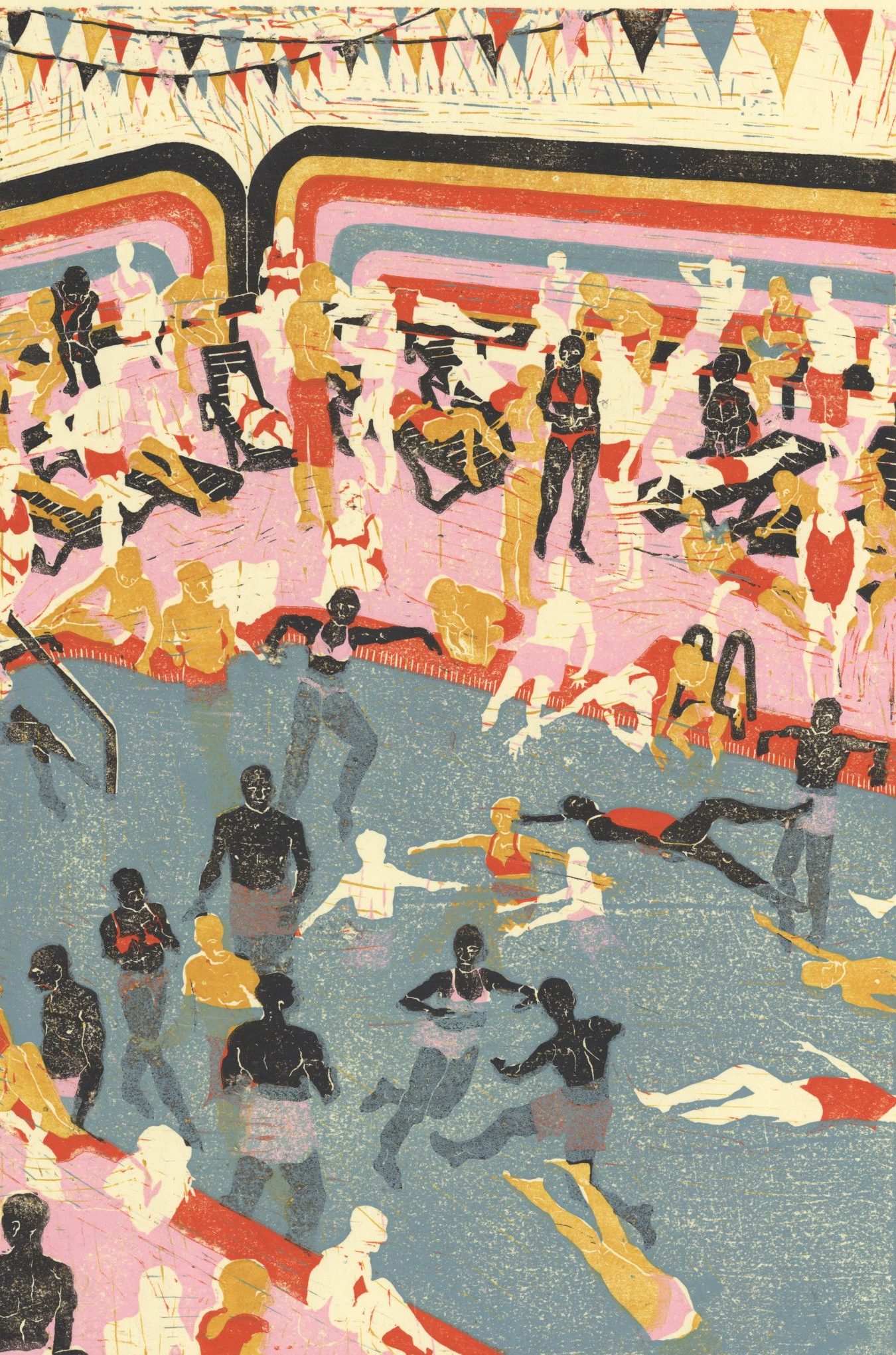

IJ: How have your experiences with visual art changed your creative processes?

HS: I actually started off as a visual artist, and visual art trained me to see. I don’t want to claim that I’m a particularly observant person, because I’ve been shocked by what I haven’t observed, but I do think that it trains you to go beyond what you think you’re seeing and to really see something. One of the first things you learn in a life drawing class is that we have an idea of what a hand is: it has five fingers, it has a palm. However, that’s not what a hand looks like in space. And sometimes with a hand in space, you can only see two fingers, or it looks more like a fist, and so you really have to rethink what your brain tells you, as opposed to what you are actually perceiving. I think visual art has really trained me to override the language that my brain wants to impose on something, and instead try to really see it. And it really trains you how to live and work as an artist, and how to deal with failure, because drawing is just constant failure. Someone like David Hockney, who has been doing this for decades now, if you watched him drawing now, you’d see him trying to feel it out, you’d see him make mistakes and then correct them, right? And so, it really teaches you that failing and then correcting is part of the perceptional process.

IJ: What is your daily writing process like?

HS: I read a lot, and I spend a lot of time taking care of various kinds of jobs that I have, so I’ll sometimes just spend the day grading and not writing. I am an editor for a magazine, West Branch, and I’ll spend the day working on the magazine. I’m always reading though, and usually I get projects in my head and then I’ll think through the project, and I’ll plan the project, and then I’ll focus on the project. So my writing tends to be really project-based. If I’m not working on a project, and I’m usually almost always working on a project, but if I’m not, then I’m reading and trying to take care of other things. I know that I’m supposed to tell people that I write every day and all that, but I don’t, and I feel terrible telling people that, but sometimes you have to do those things, and so you don’t write. I write when I feel inspired, and sometimes maybe a few weeks will go by and I haven’t written anything because I haven’t yet been inspired.

IJ: What have you learned through teaching others how to write?

HS: I think teaching writing has been the best way to learn writing. I went through an MFA program and I was workshopped a lot, and that helped, but I think when you have to articulate a concept in order to teach somebody else, that is when you really learn. That is even true for writing essays. I was given the opportunity to teach a class, Introduction to Creative Nonfiction, and at the time I had only written a few essays. In order to teach essays, I had to really think, how do I discuss this? And then I really began to want to write them more and more. So often with teaching, I’m also simultaneously teaching myself.

IJ: When you begin writing an essay, do you know what you want to include from the start? What is that process like?

HS: I really think and think and think through something, and I really sit and deliberate and imagine it and turn it around in my mind and then almost always by the time I sit down to write, I know what it is going to look like. I do draft and redraft, but I think it’s really unusual at this point for my work to take on a completely different form than the original. Usually, the revision has to do with moving parts around. I spend a good portion of any project thinking about writing a project. Maybe I’m just a ruminator or something.

I think one of the hardest things about writing is to keep yourself motivated when things aren’t successful. So maybe this is a way for me to make sure that I’m using my time wisely. I don’t have hours and hours just to write sort of randomly. I’m usually working on something for somebody.

IJ: Do you intentionally write about Sri Lanka to give a voice to your family and others? Do you find yourself writing more about things you know, or things you don’t know?

HS: In the collection, there are only two essays that directly have anything to do with Sri Lanka. And of course, that said, you know my family appears in the essays quite a bit. There’s another essay called “Lady” that does deal with Sri Lankan culture, though it’s not central to the essay. Some people argue it is, but the essay actually has to do with the name of the syndrome that my mother died of. I usually write an essay to learn. I usually have a question when I start off working on an essay. For example, for this essay that is about the syndrome that my mother died of, it’s actually named after an Oscar Wilde play, and I remember being in the hospital and the doctor was telling us about it, and I thought, That seems random, like why is it named after an Oscar Wilde play? And I had luckily studied Oscar Wilde in graduate school, and I thought, That’s so strange, because there didn’t seem to be any connection between what my mother was suffering and the play, which is Lady Windermere’s Fan, and I was like, I don’t know what the connection is. When I looked into the history, it was actually a very sad history; there was a real misunderstanding on the part of the people who named the disease. I was able to make an essay that was even deeper than the history of the naming of the disease. It became an essay about how we don’t understand other people’s suffering, that we can’t fully place ourselves in comprehending the pain other people are feeling. I’m usually working from a place of mystery. I’m certainly pulling on a lot of knowledge that I have, but often I’m using the essay to describe the process of trying to figure something out. The root word for essay is the French essayer, to try. I always like to think that I am trying to answer a question, I’m trying to acquire knowledge. I think if I knew it, it probably wouldn’t interest me.

IJ: What kind of audience do you find yourself writing for? People with similar experiences to your own, or people with really different experiences?

HS: I would hope the last one. I mean, it’s not that I wouldn’t be interested in someone with similar experiences. I have an essay that I published when I found out that my father had married someone secretly after my mother passed away, and I had really thought that could have only happened to me, only to find out, it happens to more people than you would think! For sad reasons. Sometimes people can’t make their marriages known for various reasons; because of class, or maybe because their sexual identity might have been illegal or might have caused them to be prosecuted. That’s been the great fun of writing essays, as opposed to fiction, because no one ever writes you for a fiction story and says, that happened to me! I mean, no one reads my cricket story and goes, Oh, I used to play cricket. That’s not how you relate to a piece of fiction. There’s a limited audience for the short story, and that audience shrinks for the essay, especially the type of essay that I write. So, I think most of the people that I write for are very curious about the essay, and I think those are going to be people who are really interested in the world, in ways that are probably unique to that reader.

IJ: Have you ever struggled with the ethical question of how to share your experiences even if others have very different interpretations of the same experiences?

HS: I think you can certainly give your version of something, but you have to be really clear on a few things. First of all, that it’s your version of the event. I also think you really have to go out and ask your family, or ask your friends, or get verification that what you’re seeing is what other people see. Then you need to allow the chance for those other people to come in and say, that wasn’t how I saw it. In my essay “Lady,” I gave my impression of my mother, and then I realized that might not be my sister’s impression. So I asked her, and she said that she didn’t see her the same way that I did, and I put that into the essay. It deepened the essay because it made me understand that I was operating from my own emotions and fears, and my impression of my mother. My sister didn’t share those emotions or fears, and we were in the same family, and she just didn’t see it that way. I think that’s part of being honest, which really enriches your work.

And the final thing is, I think that you always need to be willing to make yourself look bad if you’re going to make other people look bad. Ultimately, I think you have to make yourself look the worst, or if not the worst, look just as bad. Invariably, you are just as bad as the people you’re criticizing. I haven’t ever found that I really occupy a true high ground. Most of the time I have done something equally as dubious, if not more so because I probably should have known better. I think if someone clearly did something egregious but there was no room for me to write about my own complicity, I’m not sure I would write that story. I think ultimately for me, I’d rather admit that I’m as flawed as any of these people that I write about.